|

| The Hippocratic Oath http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/ body/hippocratic-oath-today.html |

Before this week, I never really thought of practicing medicine as an art. It just seemed incredibly science-based and precise. At first, calling it an art made it seem like doctors kind of messed around and tried things in the hopes that they could heal patients. But now, I understand a bit of why medicine can be called an art. The process of treating a patient or performing a surgery can be very artistic. In fact, the precision that makes medicine seem like science also makes it more like art. When doctors work, it is like an artistic performance, carefully thought through and carried out. The Hippocratic Oath that doctors take shows the gravity of the work they do.

|

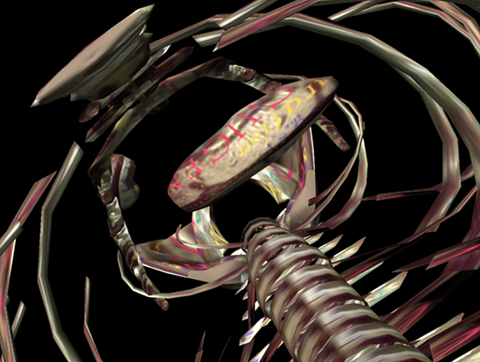

| Still from Digital Dervish, 1993 Diane Gromala and Yakov Sharir http://gromala.iat.sfu.ca/New/dervish.html |

Looking at art that uses medical technology, one thing that struck me was that for the most part, the artists use their own bodies in making their art. Some of it actually involves having surgical procedures on themselves. For example, Orlan went through plastic surgery in her artwork. This type of art seems more personal and internal than other types because the artist’s body is so often used. Diane Gromala does art and research using virtual reality and biofeedback. She is interested in studying the internal senses of the body, so although she doesn’t change her own body for art, she is exploring something deeper inside. The image on the right is from a virtual reality inside the body. Casini describes something similar in MRI, where her focus is not on the static images obtained, but the sounds and movements experienced.

The anatomy of the body has long been used in art; people have always been fascinated with the human body. Of course, this is not surprising because the body is complex and beautiful. In his article, Ingber explores the architecture of many biological structures that are similar. Because of tensegrity, stress can be distributed across structures in unexpected ways and perform certain functions. Different patterns in structures recur in many different organisms in nature. It is amazing that living things are so distinct and unique yet also have so many similarities.

A model of part of a DNA string using tensegrity. I think it's pretty cool.

|

Sources:

Casini, Silvia. "Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) as Mirror and Portrait: MRI Configurations between Science and the Arts." Configurations 19.1 (2011): 73-99. Web. 21 Apr. 2016.

Ingber, Donald E. "The Architecture of Life." Sci Am Scientific American 278.1 (1998): 48-57. Web. 21 Apr. 2016.

Medicine pt1. Youtube.com. Web. 21 Apr. 2016.

TEDxAmericanRiviera - Diane Gromala - Curative Powers of Wet, Raw Beauty. Youtube.com. Web. 21 Apr. 2016

Tyson, Peter. "The Hippocratic Oath Today." NOVA. PBS, 2001. Web. 21 Apr. 2016.